The Secret Game: The 1944 Matchup Overlooked In History

The Secret Game: The 1944 Matchup Overlooked In History

In 1944, one of the most historic matchups in the history of American sports took place — behind closed doors.

Two decades before the famed Loyola University Chicago and Texas Western basketball teams claimed national championships, another landmark moment for the integration of sports played out in North Carolina — though most of the world knew nothing about it.

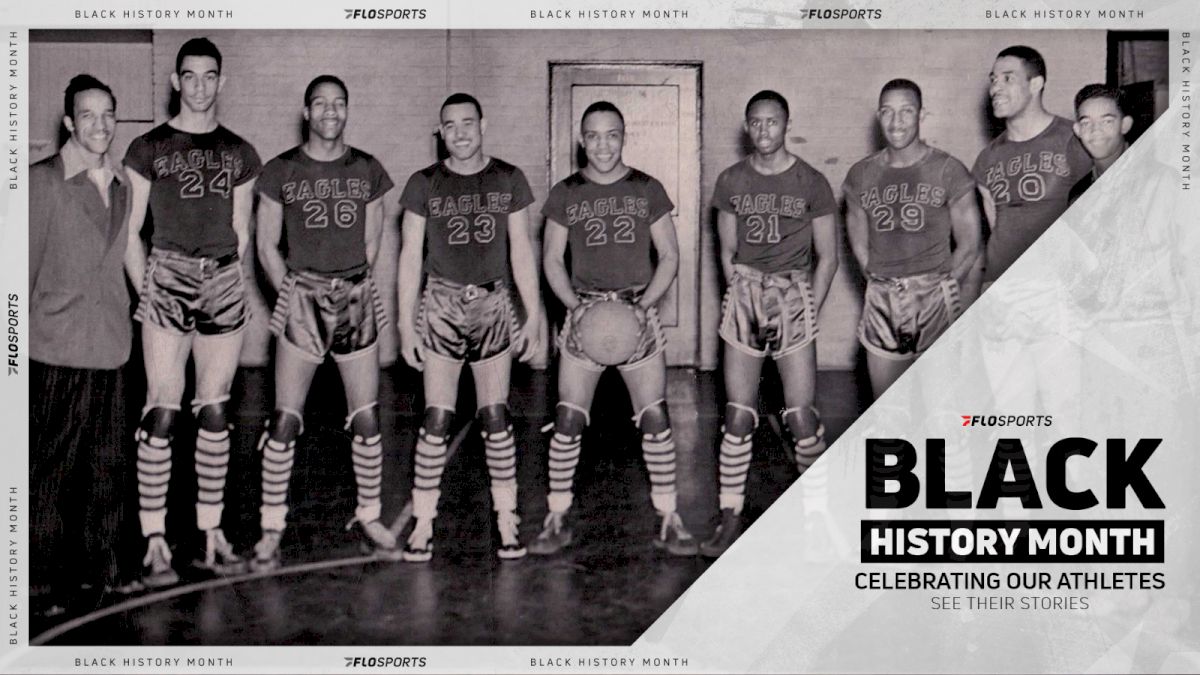

The “Secret Game” — nicknamed as such because all involved had to keep it from the public — pit Duke University’s medical school team against the dominant North Carolina College for Negroes squad.

Known today as North Carolina Central, NCCU has been one of the most consistent programs of the past half-decade under coach LeVelle Moton. The Eagles claimed the MEAC’s automatic bid into the NCAA Tournament four times since 2014, including three straight from 2017 through 2019.

North Carolina Central’s 2019 NCAA Tournament tipped off 75 years and eight days after the Secret Game, with the Eagles in the same bracket as a top-seeded Duke with future NBA star Zion Williamson. The scene was set for a historic rematch between the programs on college basketball’s grandest stage.

That is, until it wasn’t.

A North Dakota State rally in the final minute of the First Four matchup between conference champions from the MEAC and Summit League ended the prospect of a 75-year anniversary meeting between neighbors Duke and NCCU.

So much of the essence of the NCAA Tournament that has transcended a sporting event and become a cultural touchstone is rooted in the stories of the teams and athletes involved. The near-miss that denied us a Secret Game pairing also removed a platform to retell one of sport’s most significant stories.

This seeding ties into another, broader topic of programs from the HBCU conferences being sent to Dayton and the First Four more frequently than other leagues.

“The committee — I know they resumed and made a couple of addendums and changes and modified how they view certain teams in terms of the selection — I would like for them to review that as well because a lot of times to fund some of our programs we have to take on guaranteed games,” Moton said in 2019, referencing the budgetary disparities that prompt many members of the MEAC and SWAC to load up on road non-conference games.

However, the debate on the NCAA selection committee’s assessment of HBCU programs is a complex issue — a “blessing and a curse,” as Moton described it two years ago.

Something not nearly as complex is the Secret Game deserving more recognition today.

Other landmark teams and moments in the sport have gained special cultural relevance in the 21st Century: Disney produced Glory Road, a somewhat fictionalized depiction of Texas Western’s 1966 national championship, and Pres. Barack Obama invited the 1963 Loyola University Chicago champions to the White House for their 50th anniversary.

The Secret Game has gained some attention in recent years through Scott Ellsworth’s 2015 book and a 2017 documentary on Eagles coach John McClendon by Kevin Willmott.

But the circumstances of the game and its importance warrant conversation and celebration on par with sports’ most famous moments of social impact.

Played on March 12, 1944, the Secret Game preceded Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers by three years and four years prior to Pres. Harry Truman’s executive order desegregating the military.

Social racism rendered a basketball game between the teams dangerous, as Ellsworth’s 1996 article in New York Times Magazine details. Jim Crow laws made the Secret Game illegal.

The bravery necessary to make this contest happen cannot be overstated — nor can the impact McClendon had on basketball.

A winner of almost 500 games in his college coaching career, McClendon deserves to be recognized as a basketball Eddie Robinson, and mentioned in the same breath as other luminaries like John Wooden and Dean Smith.

Smith in particular reflects McClendon’s genius. The North Carolina coaching legend took influence from McClendon’s Four Corner offense, which became a signature of the Tar Heels.

Smith was also a trailblazer in that he recruited North Carolina’s first Black basketball player, Charlie Scott. That was in 1967, 23 years after NCCU and Duke players risked their safety and freedom in the Secret Game.

Kyle Kensing is a freelance sports journalist in southern California. Follow him on Twitter @kensing45.